I’m slowly working on a book about “imperfect pilgrimages”. I have walked the Cowboy Trail in northeast Nebraska, examined the remaining boundary stones of Washington DC set in 1792 by Benjamin Banneker, examined Highway 20, our longest Main Street, meditating on what Ed Ruscha refers to as “spiritual hot spots”.

Video essayist Matthew Donaldson filmed Ed Ruscha driving to his studio. Ruscha complains about a pothole he always hits. “It irritated me no end, and finally I began to anticipate it as I was approaching it, and then I started to change my attitude toward it, and it started feeling good, and I was looking towards, looking forward, to having my left front tire roll over this little depression in the road until it registered to me as a spiritual hot spot.”

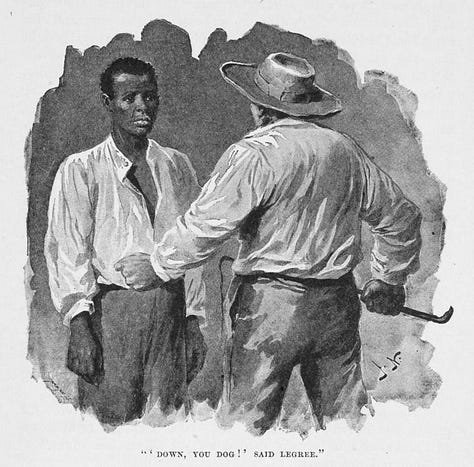

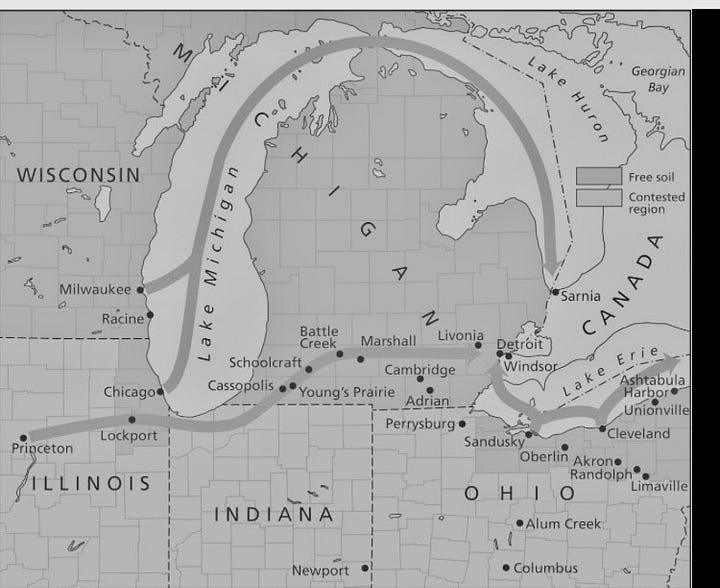

This summer, I’m going to retrace one fork of the Underground Railroad that ends at Lake Michigan at Chicago. Chicago was a hotbed of abolitionism in 1860 and the great lake the place from which the former enslaved could disperse throughout the northern Midwest and the ultimate safe haven of Canada. From there, I’ll retrace the trail back to Montgomery, Alabama a boat passage along Gun Island Chute, which, because it is a navigable waterway connected to the Alabama River, facilitated the transportation of thousands of African enslaved people into Montgomery, and became a major center of the domestic slave trade. But first, I intend to spend a little time looking into the history of the Great Lakes and the Underground Railroad, and try to bring it home, as a modern version of the reprehensible and ridiculous Simon Legree, the ICE agents, fuckwads as foul and cowardly and faceless as any depiction of the chasing of Eliza and her kid over the ice floes with dogs, both laughable and awful.

Imagine what Eliza encountered when she made it across the Ohio River to freedom in the north—seeking a new life, she encountered a sort of multicultural composite of French, British, American, and Native American people. And let’s say specifically, Quakers, valiant. They set up a system of “freedom boats” that navigated all the Great Lakes, mostly to take people to Canada.

Though it is not data, the following anecdote does seem to be the epitome of Great Lakes Underground Railway history, a rare documented example of Native American involvement with the Underground Railroad:

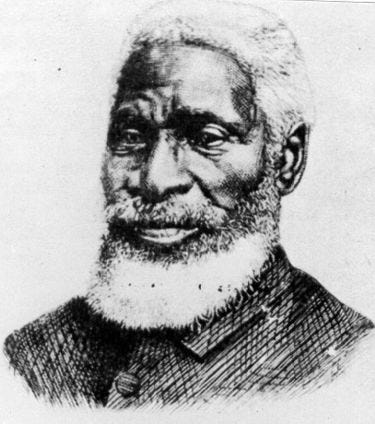

In his 1849 slave narrative, Josiah Henson, upon whom Harriet Beecher Stowe based “Uncle Tom”, describes the day that was to become one of the most memorable in his life. Henson, his wife Charlotte, and their young son were trudging, lost, through the Ohio wilderness on an old War of 1812 military road after having just escaped slavery in Kentucky. Exhausted, famished, and disoriented, the family became even more alarmed when they noticed a party of Indians watching them from a distance. Henson’s wife insisted that they turn back. But since his wife was injured and the road behind them long, Henson decided that they should continue on despite trepidation about what might result from a possible encounter with the Indians. Soon the family did come upon a Native camp farther in the woods. Communities of Wyandots, Mohawks, Shawnees, and Cayugas still claimed their settlements and hunting grounds in northern Ohio where the Hensons lost their way But rather than the danger that they had feared, the family was relieved to find a hospitable welcome in what was most likely a Shawnee or Cayuga village. Met with the residents’ apparent unfamiliarity with blacks, Henson fielded a series of questions, “to make them understand what we were, and whither we were going, and what we needed.” The villagers responded by providing the sojourners with food, comfort, and a wigwam to rest in. Equally important, the Indians provided directions, telling the Hensons that the lake they sought was twenty-five miles away and sending “some of their young men to point out the place where we were to turn off.” The Henson family would later settle in the aptly named town of Dawn, Upper Canada, after traveling a route that had brought them across the Ohio River, into Indian country, and finally, across a Great Lake.

Borders and boundaries exist in water, too.

Amazing project!!

There is a terrific Underground Railroad museum in Cincinnati. Syd took her students there. It's roughly where Margaret Garner ("the Modern Medea") was trying to cross to safety, so there's a monument on (I believe) the Kentucky side of the river.

There are certainly important parallels to note. Ohio fought to extradite Garner, since a due process trial for murder was better than being lost in the night and fog of the slaveholding South.

I mean, that's all well and good, and all, but...have you considered the Huntington West Virginia Hot Dog Trail?

https://visithuntingtonwv.org/hotdogtrail/