THE LITERATURE OF CHILDISH PARENTS WITH CHILDREN MADE OLD BEFORE THEIR TIME

Reading Henry James in Nature

The Literature of Immature Parents with Children Old Before Their Time is rich, if not explicitly framed: Paula Fox’s The Widow’s Children, Edith Wharton’s The Children, Christina Crawford’s Mommie Dearest. Dickens’ novels are full of parental messes—in Great Expectations, spoiled Belinda Pocket lets her baby play with sewing needles after being dropped for the tenth time. Jane Austen’s moms are frantic and fainting. The feckless ‘rents of Roald Dahl. Pretty much any god in Greek mythology: watch as Hera throws Hephaestus off a mountain when he turns out to be disfigured, scolds Ares.

Henry James has his share, including the always-weeping mother of Roderick Hudson, the scheming Mrs. Gareth in Spoils of Poynton, the uncle of Flora and Myles in A Turn of the Screw who is so absentee as to remain nameless. Never trust a person who sighs and says, “Children! Don’t you wish they’d stay that way?” In What Maisie Knew, little Maisie, at least in these first nine chapters I’ve read, the child of two very immature parents who hate each other so much, the courts let them divorce in the early 1890s, is on a very rapid learning curve as she’s batted back and forth like a badminton flycock.

Maisie is, for the first act of the novel, often considered an object by both characters and narrative, not a human: a “deep little porcelain cup”, “a bone” as in “of contention”, and perhaps most horribly, because it’s James himself using the term to avoid saying that Maisie was a little chubby at six, “the part of the joint at dinner that she didn’t like”. She’s a little doll—so often this—which makes Maisie’s own doll, Lisette, as round a character as any in this operation, and much more chatty.

Does anybody remember when Gilda Radner played a silent child character named Colleen who, at a therapist’s, is asked to go to the bank of dolls and toys and find first a mommy doll (Barbie), then a daddy doll (Ken) and then a Colleen doll (a roll of Scotch tape)? This is Maisie.

Maisie, I say just fifty pages in, gets to go where HJ cannot—she can be guileless, innocent, even a martyr (for now—if there’s any justice in the world, she will turn out to be what the kids these days refer to as a “Bad B”), and she can say all the things that James cannot. You know, Henry, like the word “fat”. What she is, at first, is feral, the closest cat Henry James is willing to pet while visiting this funny farm. He loves that she can say the things about awful people that He The Master cannot, and I think it scares and thrills him a little—what will she say next! Who among us has never delighted in hearing a child throw out an obscenity the meaning of which they do not know the meaning?

But if there is anything that is the opposite of nature, it is a divorce court in England at the fin-de-siecle. This book is so full of all the constructions of humans that protect us from savage nature, and, like the rescued heir to Greystoke, Maisie is a Tarzan in her parents’ well-appointed drawing room. And though she is a little savage, a barn cat in an expensive frock, she’s far more mature and measured than any parent or nanny so far.

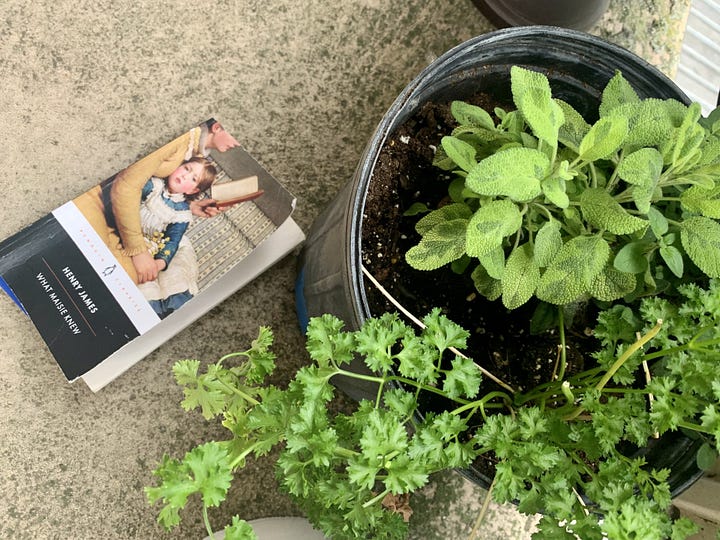

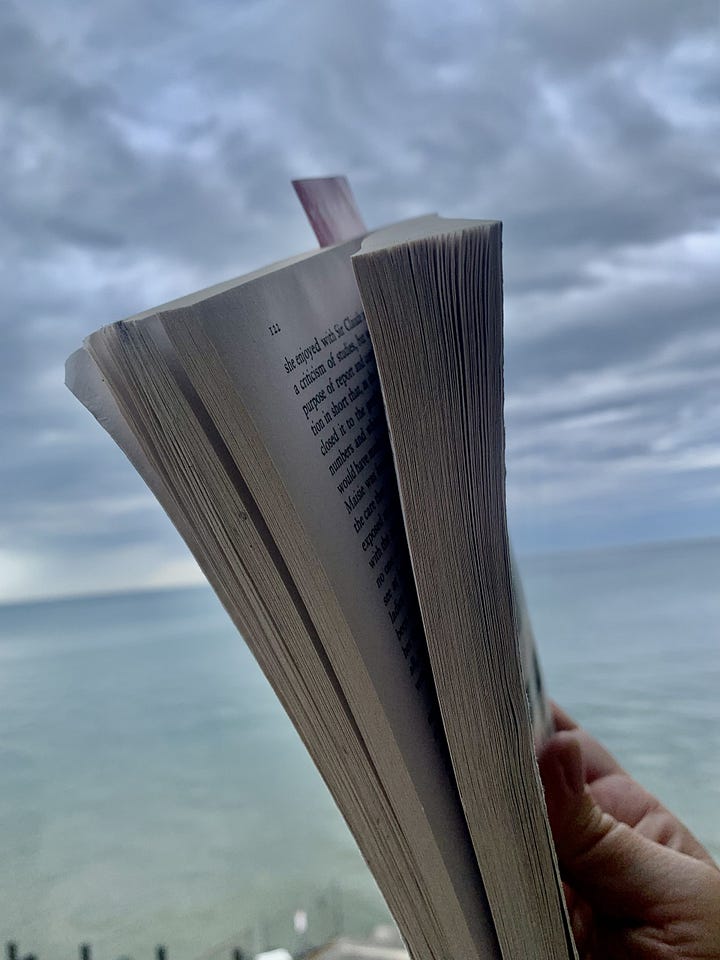

I’m done with the school year, so I’m going to be writing more about James and hoping to read him in nature, where I love him most. But I can’t lie, I haven’t been reading What Maisie Knew in the deep woods or along the hiking trail or on a riverbank, but on a balcony over sweetwater Lake Michigan, nature enough. Unintentionally, I keep leaving the book outside in rainstorms (two), or next to the place where I’ve potted some herbs for the summer on the balcony, so that even now, it looks more weathered and bloated than any of my other James paperbacks.

I'm glad you mentioned Wharton's The Children. Her later novels like that one, Glimpses of the Moon, and The Mother's Recompense were sorely neglected back before I published Edith Wharton's Prisoners of Shame.